MAKERS OF DEATH: REFLECTIONS ON THE VEIL & THE HARVEST

A TWO-PART SERIES (PART 2)

Sequoia Day O'Connell

March 2019

While Taylor Hanigosky’s suspended works in both The Veil and The Harvest are an act of withholding—a denial of the second part of the cycle, a reckoning with the absolute mid-point, Alex Mari’s durational piece An Everyday that is Invisible was a painful and honest portrayal of a full cycle. Mari’s performance was a simultaneous making and a grieving. She was the creator of a space and a time, therefore she was also the destroyer of it. There was no singular end result of the piece, it existed precisely in the space and moment the performance was rendered: the clicking sound of stacking rocks, and the resonance of wood against the wall marked the passage of moments in the piece nearer towards the inevitable with each click. Anyone who walked into that room knew who built it, and held quietly to the unreasonable prayer that it would not turn back into being just a room as it was before. Mari’s work touches on the ephemeral nature of the body--it renders each moment precious, and induces a consistent grieving process for each past moment lost, as the next is built on the lineage of the last. An Everyday that is Invisible began with a projected still of the empty room, rocks stacked neatly with bowls of fruit, baby oil, and dried flowers. As the performance came to a close, the record of its fleeting moments were contained in the oil and mashed berry footprints across the floor, and a video, now a document of all that had passed from beginning to end hovering quietly on the wall.

In Claudia Dey’s essay, Mothers as Makers of Death, she writes: I am writing—writing with the speed of an animal being chased by a larger animal. The larger animal is time. Here is the artist-mother’s bar graph: line one—the multiplying size and need of her expression—held up against line two—the rapid dissolution of time. To write is to be in conversation with yourself, to preserve a state of being so you can conclude a sequence of thinking and feeling. ³

It could be said that performances such as Mari’s are to be in conversation with the self, as well as the creation (or birth) of a self, simultaneously. A creation of a being and a death of the same being as the performance concludes— the performer as both parent and child.

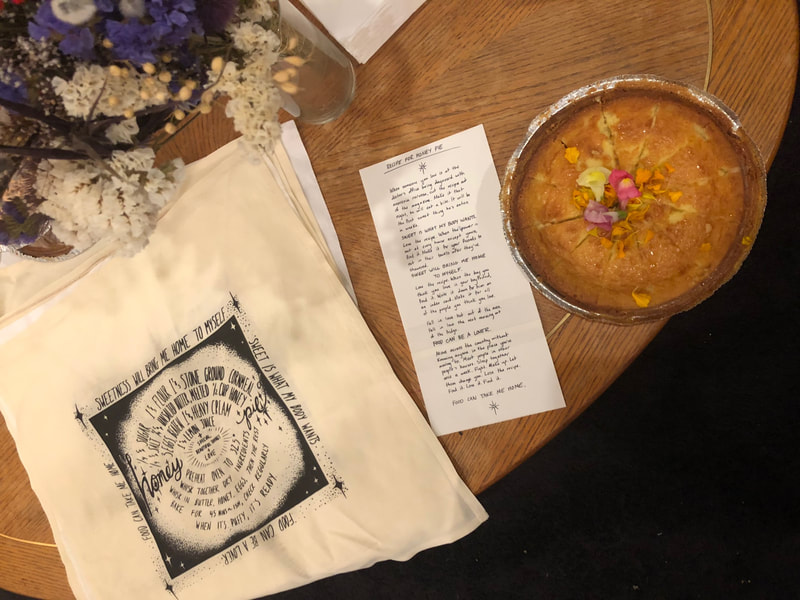

In queer communities, the job of caretaker and parent is often transferred to the self and/or to chosen family. Much like Mari’s performance, folks frequently become their own makers and sometimes, consequently, their own destroyers. There are delicious acts of love and nourishment within chosen families. Emma Kates Shaw offered just this act to show attendees, using a honey pie recipe that has come to her many times in her close community and family, both chosen and blood. Kates-Shaw uses what is traditionally seen as “women’s work” (works printed on fabric and baking) and turns it into a relational art piece. Each time Kates-Shaw makes a honey pie with a family member, friend, or lover, the pie is transformed into a record of a relationship, and of the connecting threads between the current makers and the lineage that precedes them. Kates-Shaw wrote of the first time she made the recipe:

When someone you love is at the doctor’s office being diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, cut the recipe out of the magazine. Make it that night, he will eat a bite. It will be the first thing he’s eaten in weeks…”

“...Make it for all the people you think you love.

Fall in love hot out of the oven.

Fall in love the next morning out of the fridge.

The honey pie offered a nourishment to both the physical bodies of show attendees, as well as nourishment to a lineage of queer family and relationship.

In Mothers as the Makers of Death, Claudia Dey goes on to argue, If we could perceive death as a part of pregnancy and child-rearing, we might just take women [and queer people] more seriously. ³ As a queer birth and abortion doula, I think of this essay often. Women and queer people, who are (in white, colonial frameworks) traditionally siloed to the role of caretaker, birther, or maker--are met with the surprising grey area of grief and death in the wake of reproductive health; and if chosen, birth and parenthood. Added to this is the increasing suppression of traditional midwifery practices, which is a part of the foundation of Western gynecological practices. The complexity and cultural relevance of these conversations has been flattened to serve a larger model of white femininity that is ultimately painful, dishonest, and unattainable.

Addressing practices in the other end of the cycle (death), Aya de Leon wrote Dear White People/Queridos Gringos: You Want Our Culture But You Don’t Want Us:

[y]ou arrived at the Dia De Los Muertos ceremony shipwrecked, a refugee from a culture that suppresses grief, hides death, banishes it, celebrates it only in the most morbid ways—horror movies, violent television—death is dehumanized, without loving connection, without ceremony. You arrived at El Dia De Los Muertos like a Pilgrim, starving, unequal to survival in the land of grief, and the indigenous ceremonies fed you and took you in and revived you and made a place for you at the table.

And what have you done?

Like the Pilgrims, you have begun to take over, to gentrify and colonize this holiday for yourselves.¹

With this dominant colonial narrative surrounding birth and death, there is an erosion of trust and simultaneous co-opting of indigenous and non-white intuitive knowledge, and traditional practices around the beginning and end of life. Both BBMagda and Markel Uriu’s work in The Veil and The Harvest touch upon growth in the midst of this erosion and erasure. The endangerment of native plants, in direct relation to the prevalence of invasive and white settler-introduced species is documented in Markel Uriu’s work. Uriu uses the invasive species that grow throughout the United States to craft a narrative— and ultimately, a metaphor for the body and the land in the United States (and beyond) under colonialism. Uriu’s scans of starling skins- -all of whom are derivative of 60 individual starlings a la Shakespeare, displayed with dissection pins. Death displayed in frank, clinical terms. Uriu’s precise and calculated presentation of the starlings alludes to patterns of power and control, foundational to colonialism. These works beg the question, how does one exist within a new natural world, molded in part by the violence and manipulation of colonial structures?

Markel Uriu’s scientific and sterile presentation of dead beings was the ultimate contrast to BBMagda’s psychic readings for show participants at The Harvest. Magda’s readings brought forth the exchange of warmth and intuition, a passage of the trust in a deeply held knowledge within each client that she read for. Magda created a little universe unto itself in the space, focusing in on the world and bond between her and the participant. In her artist statement, she wrote that her work provides “healing assistance, education, activation, witness, and community to all who desire to engage in the art and practice of the personal and collective metaphysical, magical, and self empowering path.” Magda finds the longing and desire in participants, digs for the root, and presents participants with themselves, already known but indelibly transformed to be seen, using herself as the medium for another’s energy and desire. Medium work is often hyperbolized and misunderstood as unscientific, where in reality, work like Magda’s offers a safe, tangible and invaluable focus on the individual as an important part of a community and lineage.

After working with many families experiencing grief and/or trauma as a part of their birth story, it is clear to me that in those moments of grief and trauma, people need vastly different things which arrive at a similar point: safety to honor one’s own body, the bodies and spirits of the ancestors who came before you, and if chosen, the lineage that continues through one’s children. With the erasure and appropriation of ancestral practices of grief, for honoring the dead, many people are left in the midst of grief without a guidebook, without capacity or permission to carry out traditional practices. Aya de Leon continues in their piece, ...[d]on’t bother to build an altar because your celebration is an altar of death, a ceremony of killing culture by appropriation..¹ Magda offers an individualized guidebook--instead of making prescriptions, her work draws from the individual and the energy resonating from within.

While The Veil was intimate but presented in a more formal art gallery setting, The Harvest created a space more resonate and reciprocal to its audience; a space where work and audience breathed as one. Corrine Manning asked of their readers, If we currently exist in a culture of longing, what does it mean to revolutionize our way of being in the world, in connection with our bodies, and to each other, through desire? ² How do we see the little deaths, and honor them, create spaces and practices for grief that are whole, that challenge colonial frameworks around birth, death, and everything in between? How do we see ourselves as the makers of our own deaths, and to love every moment of that gift of mortality? How do we connect in the physical realm, and build community, reciprocal respect, and trust in a tumultuous and fragile time?

Break the lineage of longing as TUSK does. Bear witness to each other in our fullness and vulnerability, as BBMagda does. Craft nets and accept the structures that serve us, while dismantling the ones that do not, as Taylor Hanigosky does. Present the truth and history frankly and unflinchingly as Markel Uriu does. Pull apart the history we are offered to create a record of what is, as Ko Kirk Yamahira does. Use our bodies as vessels for communication, in the physical realm (Alex Mari) and rendered (Charlie Crowell). Nourish our communities with the recipes that we hold the closest, with harvested fruits of our own labor, like Emma Kates-Shaw. Ultimately, each of these artists offer an invaluable glimpse at how to not just survive, but connect.

To read part one of this essay, please click here!

Sequoia asks that you consider donating to Open Arms Perinatal Services, a nonprofit focused on strong community-based support for women through pregnancy, birth, and early childhood. Here's a link to learn more and send your contribution!

Sequoia Day O’Connell is a Seattle curator and photographer, as well as a birth and abortion doula. They received a BA in Visual Arts and Psychology from Hampshire College in 2015, and was an organizer with Lions Main Art Collective in 2016-2017, as well as an organizer and member of the Board of Directors at The Vera Project, 2008-2013. Sequoia curated and organized the Blue Lady shows in Northampton, MA, an inclusive art and performance show that highlighted voices in the queer community, using artwork as a foundational element to build and strengthen community relationships. Intimacy is a common thread in their personal, curatorial, and professional work—their photography touches the personal and vulnerable boundaries between body and space, while their work as a birth doula offers support to pregnant people and their families during a pivotal and vulnerable moment.

Citations:

1.Dear White People/Queridos Gringos: You Want Our Culture But You Don’t Want Us – Stop Colonizing The Day Of The Dead, Aya de Leon

2. Latency, Corrine Manning

3. Mothers as the Makers of Death, Claudia Dey

Further reading:

Like a Mother, Angela Garbes

Colonialism affecting traditional midwifery practices in Mexico

Killing the Black Body, Dorothy Roberts

Why do doctors insist on practicing race-based medicine? Dorothy Roberts

Shakespeare’s Starlings--Invasive Species

BBC

NY Times 2016

NY Times 1990

In Claudia Dey’s essay, Mothers as Makers of Death, she writes: I am writing—writing with the speed of an animal being chased by a larger animal. The larger animal is time. Here is the artist-mother’s bar graph: line one—the multiplying size and need of her expression—held up against line two—the rapid dissolution of time. To write is to be in conversation with yourself, to preserve a state of being so you can conclude a sequence of thinking and feeling. ³

It could be said that performances such as Mari’s are to be in conversation with the self, as well as the creation (or birth) of a self, simultaneously. A creation of a being and a death of the same being as the performance concludes— the performer as both parent and child.

In queer communities, the job of caretaker and parent is often transferred to the self and/or to chosen family. Much like Mari’s performance, folks frequently become their own makers and sometimes, consequently, their own destroyers. There are delicious acts of love and nourishment within chosen families. Emma Kates Shaw offered just this act to show attendees, using a honey pie recipe that has come to her many times in her close community and family, both chosen and blood. Kates-Shaw uses what is traditionally seen as “women’s work” (works printed on fabric and baking) and turns it into a relational art piece. Each time Kates-Shaw makes a honey pie with a family member, friend, or lover, the pie is transformed into a record of a relationship, and of the connecting threads between the current makers and the lineage that precedes them. Kates-Shaw wrote of the first time she made the recipe:

When someone you love is at the doctor’s office being diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, cut the recipe out of the magazine. Make it that night, he will eat a bite. It will be the first thing he’s eaten in weeks…”

“...Make it for all the people you think you love.

Fall in love hot out of the oven.

Fall in love the next morning out of the fridge.

The honey pie offered a nourishment to both the physical bodies of show attendees, as well as nourishment to a lineage of queer family and relationship.

In Mothers as the Makers of Death, Claudia Dey goes on to argue, If we could perceive death as a part of pregnancy and child-rearing, we might just take women [and queer people] more seriously. ³ As a queer birth and abortion doula, I think of this essay often. Women and queer people, who are (in white, colonial frameworks) traditionally siloed to the role of caretaker, birther, or maker--are met with the surprising grey area of grief and death in the wake of reproductive health; and if chosen, birth and parenthood. Added to this is the increasing suppression of traditional midwifery practices, which is a part of the foundation of Western gynecological practices. The complexity and cultural relevance of these conversations has been flattened to serve a larger model of white femininity that is ultimately painful, dishonest, and unattainable.

Addressing practices in the other end of the cycle (death), Aya de Leon wrote Dear White People/Queridos Gringos: You Want Our Culture But You Don’t Want Us:

[y]ou arrived at the Dia De Los Muertos ceremony shipwrecked, a refugee from a culture that suppresses grief, hides death, banishes it, celebrates it only in the most morbid ways—horror movies, violent television—death is dehumanized, without loving connection, without ceremony. You arrived at El Dia De Los Muertos like a Pilgrim, starving, unequal to survival in the land of grief, and the indigenous ceremonies fed you and took you in and revived you and made a place for you at the table.

And what have you done?

Like the Pilgrims, you have begun to take over, to gentrify and colonize this holiday for yourselves.¹

With this dominant colonial narrative surrounding birth and death, there is an erosion of trust and simultaneous co-opting of indigenous and non-white intuitive knowledge, and traditional practices around the beginning and end of life. Both BBMagda and Markel Uriu’s work in The Veil and The Harvest touch upon growth in the midst of this erosion and erasure. The endangerment of native plants, in direct relation to the prevalence of invasive and white settler-introduced species is documented in Markel Uriu’s work. Uriu uses the invasive species that grow throughout the United States to craft a narrative— and ultimately, a metaphor for the body and the land in the United States (and beyond) under colonialism. Uriu’s scans of starling skins- -all of whom are derivative of 60 individual starlings a la Shakespeare, displayed with dissection pins. Death displayed in frank, clinical terms. Uriu’s precise and calculated presentation of the starlings alludes to patterns of power and control, foundational to colonialism. These works beg the question, how does one exist within a new natural world, molded in part by the violence and manipulation of colonial structures?

Markel Uriu’s scientific and sterile presentation of dead beings was the ultimate contrast to BBMagda’s psychic readings for show participants at The Harvest. Magda’s readings brought forth the exchange of warmth and intuition, a passage of the trust in a deeply held knowledge within each client that she read for. Magda created a little universe unto itself in the space, focusing in on the world and bond between her and the participant. In her artist statement, she wrote that her work provides “healing assistance, education, activation, witness, and community to all who desire to engage in the art and practice of the personal and collective metaphysical, magical, and self empowering path.” Magda finds the longing and desire in participants, digs for the root, and presents participants with themselves, already known but indelibly transformed to be seen, using herself as the medium for another’s energy and desire. Medium work is often hyperbolized and misunderstood as unscientific, where in reality, work like Magda’s offers a safe, tangible and invaluable focus on the individual as an important part of a community and lineage.

After working with many families experiencing grief and/or trauma as a part of their birth story, it is clear to me that in those moments of grief and trauma, people need vastly different things which arrive at a similar point: safety to honor one’s own body, the bodies and spirits of the ancestors who came before you, and if chosen, the lineage that continues through one’s children. With the erasure and appropriation of ancestral practices of grief, for honoring the dead, many people are left in the midst of grief without a guidebook, without capacity or permission to carry out traditional practices. Aya de Leon continues in their piece, ...[d]on’t bother to build an altar because your celebration is an altar of death, a ceremony of killing culture by appropriation..¹ Magda offers an individualized guidebook--instead of making prescriptions, her work draws from the individual and the energy resonating from within.

While The Veil was intimate but presented in a more formal art gallery setting, The Harvest created a space more resonate and reciprocal to its audience; a space where work and audience breathed as one. Corrine Manning asked of their readers, If we currently exist in a culture of longing, what does it mean to revolutionize our way of being in the world, in connection with our bodies, and to each other, through desire? ² How do we see the little deaths, and honor them, create spaces and practices for grief that are whole, that challenge colonial frameworks around birth, death, and everything in between? How do we see ourselves as the makers of our own deaths, and to love every moment of that gift of mortality? How do we connect in the physical realm, and build community, reciprocal respect, and trust in a tumultuous and fragile time?

Break the lineage of longing as TUSK does. Bear witness to each other in our fullness and vulnerability, as BBMagda does. Craft nets and accept the structures that serve us, while dismantling the ones that do not, as Taylor Hanigosky does. Present the truth and history frankly and unflinchingly as Markel Uriu does. Pull apart the history we are offered to create a record of what is, as Ko Kirk Yamahira does. Use our bodies as vessels for communication, in the physical realm (Alex Mari) and rendered (Charlie Crowell). Nourish our communities with the recipes that we hold the closest, with harvested fruits of our own labor, like Emma Kates-Shaw. Ultimately, each of these artists offer an invaluable glimpse at how to not just survive, but connect.

To read part one of this essay, please click here!

Sequoia asks that you consider donating to Open Arms Perinatal Services, a nonprofit focused on strong community-based support for women through pregnancy, birth, and early childhood. Here's a link to learn more and send your contribution!

Sequoia Day O’Connell is a Seattle curator and photographer, as well as a birth and abortion doula. They received a BA in Visual Arts and Psychology from Hampshire College in 2015, and was an organizer with Lions Main Art Collective in 2016-2017, as well as an organizer and member of the Board of Directors at The Vera Project, 2008-2013. Sequoia curated and organized the Blue Lady shows in Northampton, MA, an inclusive art and performance show that highlighted voices in the queer community, using artwork as a foundational element to build and strengthen community relationships. Intimacy is a common thread in their personal, curatorial, and professional work—their photography touches the personal and vulnerable boundaries between body and space, while their work as a birth doula offers support to pregnant people and their families during a pivotal and vulnerable moment.

Citations:

1.Dear White People/Queridos Gringos: You Want Our Culture But You Don’t Want Us – Stop Colonizing The Day Of The Dead, Aya de Leon

2. Latency, Corrine Manning

3. Mothers as the Makers of Death, Claudia Dey

Further reading:

Like a Mother, Angela Garbes

Colonialism affecting traditional midwifery practices in Mexico

Killing the Black Body, Dorothy Roberts

Why do doctors insist on practicing race-based medicine? Dorothy Roberts

Shakespeare’s Starlings--Invasive Species

BBC

NY Times 2016

NY Times 1990