ART OF THE POSSIBLE

Cable Griffith

June 2014

What follows is Seattle painter Cable Griffith's catalogue essay for Tim Cross' solo show, Syzygy, at Bridge Productions/LxWxH.

When I arrive at Tim Cross’s house and studio, the front door is open and I can hear him calling me in before I even start up the stairs. Through the front door, his living room acts as a combination of lounge, studio, art gallery, and installation. Scanning the space, it can be sometimes difficult to know where art ends and living space begins. An accumulation of other artists’ projects also live here, left over from previous house exhibitions (Valley and Taylor). But today, my attention is drawn to Tim’s recent series of acrylic transfers on silk, casually draped along the walls.

I knew Tim’s artwork before we ever met in person. In fact, I believe that one of the first things I said to him was, “Hey, I like your work.” Back around 2007, Tim was making what I’d call “machine-scapes”, painted over a white spatial void, combining references to landscape and mechanical schematics. Since then, the internal pictorial architecture has spilled outward into three dimensions. And now in retrospect, his hybrid spaceship dwellings feel like a metaphor for an exploration that was meant to push far beyond framed panels, paint, and pencils.

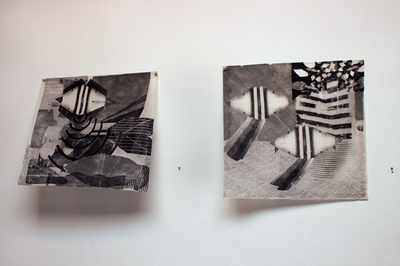

Since that early work, Tim has continually pursued and pushed ideas into unexpected territory. The structures that were once contained in a flat space eventually moved onto the wall. Shapes that were once contained within an image expanded out, sometimes nesting images within them. Something had turned inside out, mostly exposed. What was once somewhat polished, became much more raw. And then around 2011, Tim’s mostly additive process soon became one of removal and erasure.

Rather than carefully building towards a cohesive image, Tim started off by printing photographs onto aluminum and attacking each one through a process of destructive drawing. Scratching, scraping, and dissolving through the images, exposing the raw, reflective metal below. Tim was able to build a presence of form within the photographs through an aggressive removal of surface. Sharply cutting the actual into the illusionary. I felt a darkness from these pieces, but also an optimism. Many of the more playful elements in the previous work had evaporated, leaving a stark reality in its place. The results could be unsettling at times, but felt courageous and real. A few of these have been exhibited over the last few years, but I’ve sensed that Tim has mostly kept his energy on the work, in the studio.

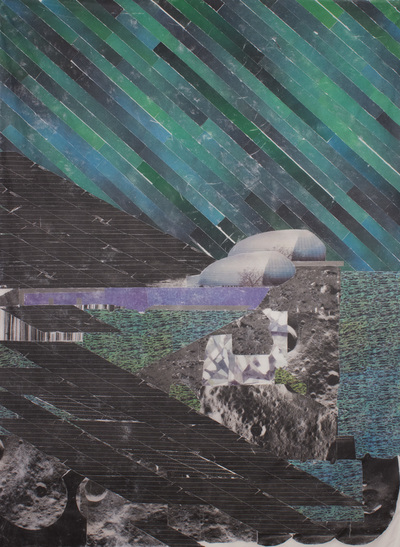

All of this leads up to Tim’s most recent work, hanging in his living room during my visit to his home and studio. I had seen occasional process images of these online and was eager to see them for myself. At once, I recognized an exciting combination of familiarity and freshness. Hanging like futuristic tapestries, the repetitive patterning establishes a firm flatness on the silk surface. But the arranged shapes add up to create fantastical scenes of another world (dimension?). Scenes of flying crafts, alien terrain, and impossible cities are constructed from carefully cut image bits. In a way, they seem to have all the elements of a classic Science Fiction book cover.

However, Tim seems to be in careful control of how much information he is willing to nail down, or rather, float freely. Each scene is like a cubist collage made from borrowed images. Each fragment has just enough photographic or descriptive information to suggest a source, but not name it. Tim’s ability to take us to the threshold of identification (and not surpass it) keeps me in a perpetual state of wonder. Although each bit suggests a source, its mystery is well kept. And these bits add up to create new nameless forms and places. This is a masterful orchestration of parts to whole, that allows for a special kind of immersion. It’s hard to stop looking at them.

Considering my knowledge of Tim’s previous work, methods, and imagery, I find that his past is all here. As if every aspect of his previous of work has found a way to cohabitate together in a new but familiar form. The compositions are formed through an accretion of cut photos and patterns, adhered to the silk with an acrylic transfer process. Deeply inspired by work of Robert Rauschenberg, Tim has been experimenting with this method for a while. Using imagery found in magazines (mostly National Geographic), Tim makes copies and cuts out pieces, saving them for later use. His studio is scattered with stacks and folders full of these bits. A table in the center of his studio is covered with loose arrangements of cut-outs, acting as a sort of staging ground for putting the puzzle pieces together. Tim picks up an elongated colorful slice of cut paper and says, “This is my brush mark.” I remark how it feels like he’s extracted words or sentence fragments from their original sources to create new stories. His painting palette of the past has been replaced by an accumulating archive of found images.

It made me think of sample-based music, in which songs are created from extracted parts of other songs. The birth of hip hop music and the prevalence of sampling had a lot to do with access (records over instruments). As a listener, the identification of a sample’s source was satisfying because it both connected you to the artist’s influences, and tested one’s awareness of music history. It seems significant to me that Tim would remove his hand so much from the process and choose to create scenes of new worlds through the manipulation of existing pictures from our image-saturated culture. Similar to Rauschenberg, Tim is creating something new while reflecting a photographic history back at us.

Tim’s image/mark-making and return to his sci-fi roots would feel like a homecoming if it didn’t seem so poised to keep moving ahead. Ray Bradbury once described science fiction as “art of the possible” making a distinction between it and “fantasy”. Tim’s own speculative realism communicates through a strong blend of narrative, process, historical self-awareness, and an unrelenting questioning of conventions. I can’t wait to see where he takes us next, but I’m happy to stay here with him a while.

Cable Griffith

June 2014

When I arrive at Tim Cross’s house and studio, the front door is open and I can hear him calling me in before I even start up the stairs. Through the front door, his living room acts as a combination of lounge, studio, art gallery, and installation. Scanning the space, it can be sometimes difficult to know where art ends and living space begins. An accumulation of other artists’ projects also live here, left over from previous house exhibitions (Valley and Taylor). But today, my attention is drawn to Tim’s recent series of acrylic transfers on silk, casually draped along the walls.

I knew Tim’s artwork before we ever met in person. In fact, I believe that one of the first things I said to him was, “Hey, I like your work.” Back around 2007, Tim was making what I’d call “machine-scapes”, painted over a white spatial void, combining references to landscape and mechanical schematics. Since then, the internal pictorial architecture has spilled outward into three dimensions. And now in retrospect, his hybrid spaceship dwellings feel like a metaphor for an exploration that was meant to push far beyond framed panels, paint, and pencils.

Since that early work, Tim has continually pursued and pushed ideas into unexpected territory. The structures that were once contained in a flat space eventually moved onto the wall. Shapes that were once contained within an image expanded out, sometimes nesting images within them. Something had turned inside out, mostly exposed. What was once somewhat polished, became much more raw. And then around 2011, Tim’s mostly additive process soon became one of removal and erasure.

Rather than carefully building towards a cohesive image, Tim started off by printing photographs onto aluminum and attacking each one through a process of destructive drawing. Scratching, scraping, and dissolving through the images, exposing the raw, reflective metal below. Tim was able to build a presence of form within the photographs through an aggressive removal of surface. Sharply cutting the actual into the illusionary. I felt a darkness from these pieces, but also an optimism. Many of the more playful elements in the previous work had evaporated, leaving a stark reality in its place. The results could be unsettling at times, but felt courageous and real. A few of these have been exhibited over the last few years, but I’ve sensed that Tim has mostly kept his energy on the work, in the studio.

All of this leads up to Tim’s most recent work, hanging in his living room during my visit to his home and studio. I had seen occasional process images of these online and was eager to see them for myself. At once, I recognized an exciting combination of familiarity and freshness. Hanging like futuristic tapestries, the repetitive patterning establishes a firm flatness on the silk surface. But the arranged shapes add up to create fantastical scenes of another world (dimension?). Scenes of flying crafts, alien terrain, and impossible cities are constructed from carefully cut image bits. In a way, they seem to have all the elements of a classic Science Fiction book cover.

However, Tim seems to be in careful control of how much information he is willing to nail down, or rather, float freely. Each scene is like a cubist collage made from borrowed images. Each fragment has just enough photographic or descriptive information to suggest a source, but not name it. Tim’s ability to take us to the threshold of identification (and not surpass it) keeps me in a perpetual state of wonder. Although each bit suggests a source, its mystery is well kept. And these bits add up to create new nameless forms and places. This is a masterful orchestration of parts to whole, that allows for a special kind of immersion. It’s hard to stop looking at them.

Considering my knowledge of Tim’s previous work, methods, and imagery, I find that his past is all here. As if every aspect of his previous of work has found a way to cohabitate together in a new but familiar form. The compositions are formed through an accretion of cut photos and patterns, adhered to the silk with an acrylic transfer process. Deeply inspired by work of Robert Rauschenberg, Tim has been experimenting with this method for a while. Using imagery found in magazines (mostly National Geographic), Tim makes copies and cuts out pieces, saving them for later use. His studio is scattered with stacks and folders full of these bits. A table in the center of his studio is covered with loose arrangements of cut-outs, acting as a sort of staging ground for putting the puzzle pieces together. Tim picks up an elongated colorful slice of cut paper and says, “This is my brush mark.” I remark how it feels like he’s extracted words or sentence fragments from their original sources to create new stories. His painting palette of the past has been replaced by an accumulating archive of found images.

It made me think of sample-based music, in which songs are created from extracted parts of other songs. The birth of hip hop music and the prevalence of sampling had a lot to do with access (records over instruments). As a listener, the identification of a sample’s source was satisfying because it both connected you to the artist’s influences, and tested one’s awareness of music history. It seems significant to me that Tim would remove his hand so much from the process and choose to create scenes of new worlds through the manipulation of existing pictures from our image-saturated culture. Similar to Rauschenberg, Tim is creating something new while reflecting a photographic history back at us.

Tim’s image/mark-making and return to his sci-fi roots would feel like a homecoming if it didn’t seem so poised to keep moving ahead. Ray Bradbury once described science fiction as “art of the possible” making a distinction between it and “fantasy”. Tim’s own speculative realism communicates through a strong blend of narrative, process, historical self-awareness, and an unrelenting questioning of conventions. I can’t wait to see where he takes us next, but I’m happy to stay here with him a while.

Cable Griffith

June 2014