IMPOSSIBLE DISTANCES: SCIENCE FICTION, ESTRANGEMENT, AND PHOTOGRAPHY

Kevin Swann

April 2013

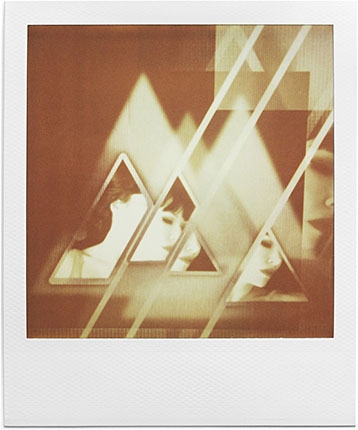

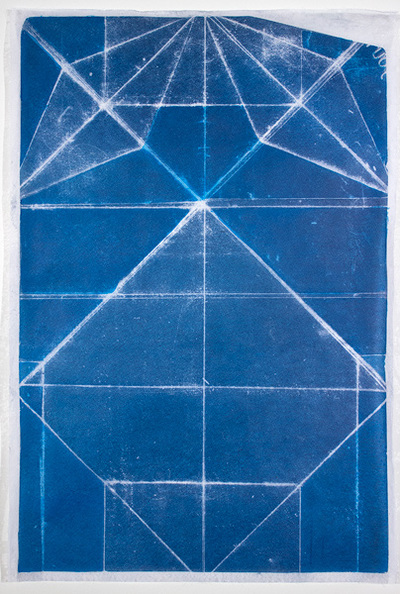

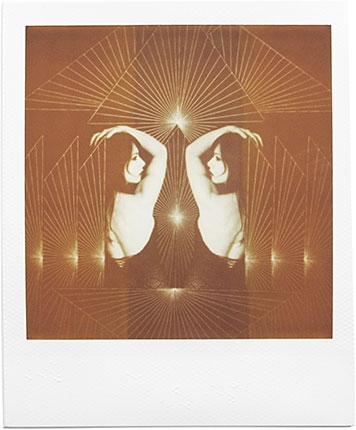

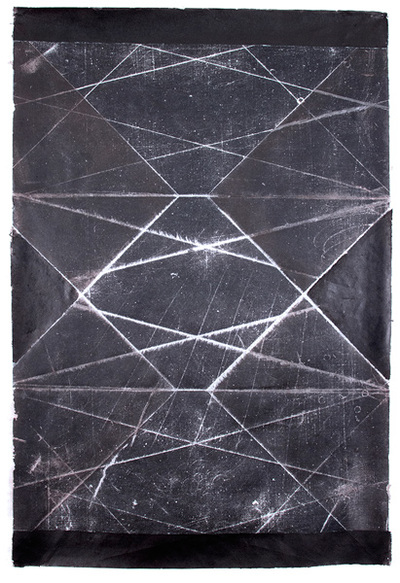

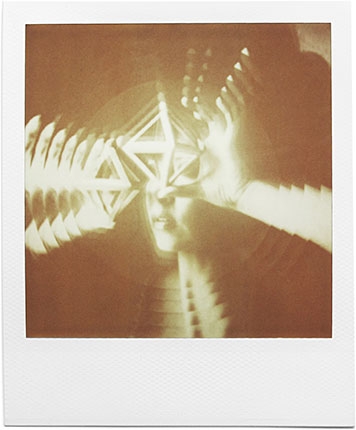

This piece of speculative prose by Kevin Swann accompanied our 2013 curated box set, Simulate, featuring original work by Erin Frost and Tim Cross. This collaboration involved stories around symmetry, outer versus inner space, the illusion of time, and themes relating to altered photography as dissimulation, ways of seeing, and what it means to be human.

TO DEMOLISH THE IMPERICAL

A science fictional text is a stage for a particular kind of conflict: the dialectical confrontation of cognition and estrangement. [1] What makes cognition possible in science fiction is the construction of a textual world that is both comprehensible and empirically valid to the reader. What makes estrangement possible is the introduction of the novum (literally, the “new thing”) into this quotidian, empirically commonplace, textual world. Science fictional nova, when introduced into this world, “totally reconfigure the mundane environment of empirical reality and thus critically estrange” it. [2] Hence, science fiction describes a set of generic tendencies and effects (like the critical estrangement of a formerly explicable world) that can be found in other artistic media particularly, as I shall argue, photography. A distinction: a science fictional impulse in art has nothing to do with the subject of an artwork, which may or may not evoke weakly or strongly the visual vocabulary of science fiction. Rather, the science fictional element of art remains the presence of a novum and its estrangement of the empirical. Thus, science fictional is any work that demonstrates that the empirical is an effect of the historical, in order to expose the real as constructed, contingent, and strange.

THE EMPIRE NEVER ENDED

Science fiction takes as a problem that which is subjectively experienced as natural and unproblematic. Time is a procession of empty moments measured by clock and calendar. The past exists as artifacts: books, buildings, scars. The future is always already the present just as the present is always already the past. Philip K Dick’s VALIS demolishes this understanding of time by exposing its protagonist, Horselover Fat, to the Black Iron Prison: an image of a geometrical shape which joins the novel’s present and first century Rome into the “two-world-superimposition.”[3] As if to restate the estranging power of science fiction, Fat himself discovers the Black Iron Prison in a sci-fi book. “Once, in a cheap science fiction novel, Fat had come across a perfect description of the Black Iron Prison, but set in the far future. So if you superimposed the past (ancient Rome) over the present (California in the twentieth century) and superimposed the far future […] over that, you got the Empire, as the supra- or trans-temporal constant.”[4] Time itself is not as empirically natural as it would seem and the ideology that naturalizes the passage of time is, to use Dick’s terminology, evidence that the empire never ended.

TIME IS AN ILLUSION. THIS IS ITS MOMENT.

Dick’s goal is to estrange our rational, scientific understanding of time—what Benedict Anderson calls “homogenous, empty time”— by putting it into dialectical opposition with Messianic Time, “a simultaneity of past and future in an instantaneous present.”[5] These versions of time act as the mode of temporality for their respective epistemological orders. In a regime of secular time, moments are a dispassionate procession of empty and discrete units. Simultaneity is mere coincidence. Time is simple passage and its remains are artifacts. In a regime of Messianic Time, every moment is an instance of pure potentiality marked by prophecy and fulfillment. Simultaneity is prefiguration. Time is a passionate message and its remains are relics. However, dialectical opposition does not mean complete alterity. Rather, it implies a kind of similarity across otherness. If the Black Iron Prison is a figure for Messianic Time and the calendar is the figure of empty time, then Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History is the figure mediating the two; “Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage.”[6] The past is always already a part of a simultaneous present because the present is always accompanied by the past.

MESSIANIC TIME: MESSIANIC SPACE

Consider the religious artwork of the pre-renaissance era as the visual counterpart to Messianic Time. Everything in the image occurs at once, even when those events do not happen at what, in modernity, we would call “the same time”. Adam and Moses appear with Jesus and perhaps even the current monarch. Messianic art depicts all moments in historical simultaneity as a continually unfolding instance of messianic prefiguration and fulfillment. Space was key to this figuration. Messianic art depicts scenes of simultaneous moments occurring in a spatiotemporal instant with neither depth nor distance. The appearance of perspective destroyed the flat plane of messianic simultaneity and thus instantiated homogeneous empty time in a similarly homogeneous and empty representational space. Increasingly, realist movements in art attempted to render moments as static fragments of a now that is always already over, as crystallized shards of homogeneous empty time. If the product of messianic art was on the order of a religious artifact, the product of realist art is on the order of evidence. And therein lies the power of photography. Photography is the most thoroughly estranging medium because the photograph itself is the physical effect of a world that exists in time and space.

THEY ARE NOT WHERE WE ARE

Few science fiction texts have taken up space as an object of critical examination, that is, as something to be estranged. Of note is China Miéville’s The City and The City, which uses the harsh empiricism of the police procedural to examine the ideological construction of space. Two cities, Besźel and Ul Qoma, overlap spatially yet are invisible to one another’s citizens due to an ideologically enforced collective blindness.[7] The cities’ inhabitants occupy a world in which alterity and space are co-constitutive. The alter is both other and distant to the point of invisibility while the familiar is both known and exists within the domain of the sensible. Miéville is positing the spatial equivalent to messianic time: the science fictional space. If a messianic time is one in which moments are dense and over-determined, then science fictional space is one in which distance and nearness are similarly over-determined. Science fictional space is brimming with associations, differences, and lines of flight that collapse distance into a dense here: a topology of contingent, shifting, and meaningful arrangements. Besźel and Ul Qoma, like the Black Iron Prison, estrange the subjective experience of space by imbricating it into a historically contingent organization of meaning.

VISUALIZING VISION

Where authority organizes a way of seeing, as it does in Besźel and Ul Qoma, therein is visuality: the form of mediation native to a mode of power. The effect of visuality is to collapse the empirically “real” into the ideologically necessary. Visuality has as much to do with the ability of an artist to render time as messianic as it does with a general to “visualize” the battlefield. Both render the sensible world in ways that bind it to a particular mode of authority. In both cases, rendering space is intrinsic to instantiating authority because modes of power demand modes of organizing space. To render space as flat or to arrange it panoptically is to inscribe power into the matrix of the empirical world. Space becomes over-determined—hidden spaces, productive spaces, silent spaces, empty spaces—each making and remaking authority. Visualization’s ironies are two-fold. First, it is most powerful when what it sees would be otherwise invisible. A general can see the battlefield, but a general that sees the battlefield as a location on a map as well as a conjunction of training, supplies, psychology, and chance is a visionary. Second, it always invites other modes of visualization: counter-visualities.

SPACE IS THE PLACE

Photography is rational scientific modernity’s mode of visuality in much the same way that messianic art was the mode of visuality before the era of secularization. In its rendering of space, photography extends the renaissance introduction of perspective and thus establishes a form of art that can be considered the other to messianic art. The artistic elaboration of a flat instantaneous present is in dialectical opposition to photography’s apprehension of a singular moment in time and space. Prior to its emergence as an art form, photographs existed on the register of evidence of the existence of the past itself. Photographs were “melancholy objects” attesting to the certainty that during some real moment, light reflected off of an object—a newborn or loved one, a self in youthful vigor—and onto a negative.[9] Over time, photography came to also exist on the register of an art medium. Its artistic power came from its ability to extend human sense perception into space (which the photograph constituted as a rational and scientifically explicable real space) and its ability to find meaningful patterns within that space. Photographic space becomes the signifier of the real by which photography gains its ability to estrange and alienate.

PHOTOGRAPHY AS ALIENATION

As a medium, photography’s ultimate content is not images but experiences. The photograph itself is the result of the interaction of light and chemistry. If the photograph exists in the present then the moment it depicts must have happened in the past. To regard a photo in the present is to incite an emotional, aesthetic, or cognitive experience of an event which occurred in the past and for which one may not have even been present. But the experience of regarding a photograph in no way resembles the original moment. In Deleuzian terms, a moment is the sum of a multiplicity of elements in becoming, each moving along lines of flight at a variety of speeds and intensities. A photograph diminishes that difference and movement by rendering it into a static image in two dimensions. Under a regime of private property, though, the discrepancy between the image and the moment diminishes the moment, and not the image, precisely because the image, and not the moment, can be owned. Experiences become images which may be exchanged for themselves ad infinitum while real moments, which cannot be exchanged, become distant and diminished as if seen through the viewfinder. “The system becomes weightless”.[10]

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC CONSCIOUSNESS

Alienation is central to the popularity of photography. Consider the different reception to two similar photo essays, Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives (1890), and Eudora Smithe’s All God’s Children (1885). Both documented the inhabitants of urban slums and both benefitted from recent photographic advancements. Riis was an early adopter of the magnesium flash, without which he would have never been able to properly expose photographs in the darkened slums of New York’s Lower East Side.[11] Smithe, an apprentice of Louis Daguerre, had improved the Daguerreotype process in such a way as to include both the photographer and the camera in the final image.[12] Riis’ work was published to critical acclaim and even prompted then Governor Roosevelt to improve sanitation and plumbing in New York’s slums. Smithe’s images of London’s East End, however, were met with outrage from the bourgeois photograph consuming community. A side effect of Smithe’s process was that her photographs included all of the subjective thickness and “elements in becoming” present in the moments they depicted, including the bourgeoisie themselves attempting to subsume those moments (via their images) into the regime of private property.[13, 14] She had reproduced a real moment when her audience wanted a photograph.

THE POLITICS OF SEEING

Reaction to All God’s Children underlines the social need to make distinctions between kinds of images. Before photography was legitimated as an art form, it existed as evidence of the world that, paradoxically, it produced. Such photography factualized. Images were deployed as evidence of the empirical fact of the rational world and its ideology. At the same time, such images came to constitute a mode of identifying reality itself: real is that which conforms to its image.[14] Smitheotype images do not look real despite being the most valid representations of the real in existence. The fact that the ghostly, streaking after-images of the bourgeois photo-buying public and the vague clouds of linguistic construction in Smithe’s work do not look real made it easy to dismiss them as unreal. There was, then, an aesthetic need to censor Smithe’s work. There was a political need to censor her work as well. Had it been taken as factual, All God’s Children would have destabilized the social fabric of 19th century western capitalism by implicating the capitalist class in the production of poverty. Such censorship is no longer necessary because images that threaten to destabilize a social order can be described as merely art.

TO DEMOLISH THE VISUAL

Photography can be a stage for a particular kind of conflict: the dialectical confrontation of vision and estrangement. It is tempting to say that all photography is science fictional because all images estrange real moments by reducing their subjective thickness into static, two-dimensional objects. However, that would be to forget that there are two orders of images: images which factualize and images which dissimulate. By canonizing photography as art, we separate factualizing from dissimulating images. On the one hand, this restricts some images’ ability to dissimulate. However, by granting the honorific “art” we put these images into conversation with truth, even as we remove them from conversation with fact. This is the great strength of art. It is not fact therefore it is not threatening. The nova that such images introduce are less threatening as art much as science fictional nova are less threatening as unserious genre literature. Because they are less threatening we admit these images into ourselves. We allow them to work us over. Images then have a duty to be more science fictional, to estrange more thoroughly and purposefully, and to do so not as mere objects of art, but as depictions of a real beyond fact.

TO DEMOLISH THE IMPERICAL

A science fictional text is a stage for a particular kind of conflict: the dialectical confrontation of cognition and estrangement. [1] What makes cognition possible in science fiction is the construction of a textual world that is both comprehensible and empirically valid to the reader. What makes estrangement possible is the introduction of the novum (literally, the “new thing”) into this quotidian, empirically commonplace, textual world. Science fictional nova, when introduced into this world, “totally reconfigure the mundane environment of empirical reality and thus critically estrange” it. [2] Hence, science fiction describes a set of generic tendencies and effects (like the critical estrangement of a formerly explicable world) that can be found in other artistic media particularly, as I shall argue, photography. A distinction: a science fictional impulse in art has nothing to do with the subject of an artwork, which may or may not evoke weakly or strongly the visual vocabulary of science fiction. Rather, the science fictional element of art remains the presence of a novum and its estrangement of the empirical. Thus, science fictional is any work that demonstrates that the empirical is an effect of the historical, in order to expose the real as constructed, contingent, and strange.

THE EMPIRE NEVER ENDED

Science fiction takes as a problem that which is subjectively experienced as natural and unproblematic. Time is a procession of empty moments measured by clock and calendar. The past exists as artifacts: books, buildings, scars. The future is always already the present just as the present is always already the past. Philip K Dick’s VALIS demolishes this understanding of time by exposing its protagonist, Horselover Fat, to the Black Iron Prison: an image of a geometrical shape which joins the novel’s present and first century Rome into the “two-world-superimposition.”[3] As if to restate the estranging power of science fiction, Fat himself discovers the Black Iron Prison in a sci-fi book. “Once, in a cheap science fiction novel, Fat had come across a perfect description of the Black Iron Prison, but set in the far future. So if you superimposed the past (ancient Rome) over the present (California in the twentieth century) and superimposed the far future […] over that, you got the Empire, as the supra- or trans-temporal constant.”[4] Time itself is not as empirically natural as it would seem and the ideology that naturalizes the passage of time is, to use Dick’s terminology, evidence that the empire never ended.

TIME IS AN ILLUSION. THIS IS ITS MOMENT.

Dick’s goal is to estrange our rational, scientific understanding of time—what Benedict Anderson calls “homogenous, empty time”— by putting it into dialectical opposition with Messianic Time, “a simultaneity of past and future in an instantaneous present.”[5] These versions of time act as the mode of temporality for their respective epistemological orders. In a regime of secular time, moments are a dispassionate procession of empty and discrete units. Simultaneity is mere coincidence. Time is simple passage and its remains are artifacts. In a regime of Messianic Time, every moment is an instance of pure potentiality marked by prophecy and fulfillment. Simultaneity is prefiguration. Time is a passionate message and its remains are relics. However, dialectical opposition does not mean complete alterity. Rather, it implies a kind of similarity across otherness. If the Black Iron Prison is a figure for Messianic Time and the calendar is the figure of empty time, then Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History is the figure mediating the two; “Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage.”[6] The past is always already a part of a simultaneous present because the present is always accompanied by the past.

MESSIANIC TIME: MESSIANIC SPACE

Consider the religious artwork of the pre-renaissance era as the visual counterpart to Messianic Time. Everything in the image occurs at once, even when those events do not happen at what, in modernity, we would call “the same time”. Adam and Moses appear with Jesus and perhaps even the current monarch. Messianic art depicts all moments in historical simultaneity as a continually unfolding instance of messianic prefiguration and fulfillment. Space was key to this figuration. Messianic art depicts scenes of simultaneous moments occurring in a spatiotemporal instant with neither depth nor distance. The appearance of perspective destroyed the flat plane of messianic simultaneity and thus instantiated homogeneous empty time in a similarly homogeneous and empty representational space. Increasingly, realist movements in art attempted to render moments as static fragments of a now that is always already over, as crystallized shards of homogeneous empty time. If the product of messianic art was on the order of a religious artifact, the product of realist art is on the order of evidence. And therein lies the power of photography. Photography is the most thoroughly estranging medium because the photograph itself is the physical effect of a world that exists in time and space.

THEY ARE NOT WHERE WE ARE

Few science fiction texts have taken up space as an object of critical examination, that is, as something to be estranged. Of note is China Miéville’s The City and The City, which uses the harsh empiricism of the police procedural to examine the ideological construction of space. Two cities, Besźel and Ul Qoma, overlap spatially yet are invisible to one another’s citizens due to an ideologically enforced collective blindness.[7] The cities’ inhabitants occupy a world in which alterity and space are co-constitutive. The alter is both other and distant to the point of invisibility while the familiar is both known and exists within the domain of the sensible. Miéville is positing the spatial equivalent to messianic time: the science fictional space. If a messianic time is one in which moments are dense and over-determined, then science fictional space is one in which distance and nearness are similarly over-determined. Science fictional space is brimming with associations, differences, and lines of flight that collapse distance into a dense here: a topology of contingent, shifting, and meaningful arrangements. Besźel and Ul Qoma, like the Black Iron Prison, estrange the subjective experience of space by imbricating it into a historically contingent organization of meaning.

VISUALIZING VISION

Where authority organizes a way of seeing, as it does in Besźel and Ul Qoma, therein is visuality: the form of mediation native to a mode of power. The effect of visuality is to collapse the empirically “real” into the ideologically necessary. Visuality has as much to do with the ability of an artist to render time as messianic as it does with a general to “visualize” the battlefield. Both render the sensible world in ways that bind it to a particular mode of authority. In both cases, rendering space is intrinsic to instantiating authority because modes of power demand modes of organizing space. To render space as flat or to arrange it panoptically is to inscribe power into the matrix of the empirical world. Space becomes over-determined—hidden spaces, productive spaces, silent spaces, empty spaces—each making and remaking authority. Visualization’s ironies are two-fold. First, it is most powerful when what it sees would be otherwise invisible. A general can see the battlefield, but a general that sees the battlefield as a location on a map as well as a conjunction of training, supplies, psychology, and chance is a visionary. Second, it always invites other modes of visualization: counter-visualities.

SPACE IS THE PLACE

Photography is rational scientific modernity’s mode of visuality in much the same way that messianic art was the mode of visuality before the era of secularization. In its rendering of space, photography extends the renaissance introduction of perspective and thus establishes a form of art that can be considered the other to messianic art. The artistic elaboration of a flat instantaneous present is in dialectical opposition to photography’s apprehension of a singular moment in time and space. Prior to its emergence as an art form, photographs existed on the register of evidence of the existence of the past itself. Photographs were “melancholy objects” attesting to the certainty that during some real moment, light reflected off of an object—a newborn or loved one, a self in youthful vigor—and onto a negative.[9] Over time, photography came to also exist on the register of an art medium. Its artistic power came from its ability to extend human sense perception into space (which the photograph constituted as a rational and scientifically explicable real space) and its ability to find meaningful patterns within that space. Photographic space becomes the signifier of the real by which photography gains its ability to estrange and alienate.

PHOTOGRAPHY AS ALIENATION

As a medium, photography’s ultimate content is not images but experiences. The photograph itself is the result of the interaction of light and chemistry. If the photograph exists in the present then the moment it depicts must have happened in the past. To regard a photo in the present is to incite an emotional, aesthetic, or cognitive experience of an event which occurred in the past and for which one may not have even been present. But the experience of regarding a photograph in no way resembles the original moment. In Deleuzian terms, a moment is the sum of a multiplicity of elements in becoming, each moving along lines of flight at a variety of speeds and intensities. A photograph diminishes that difference and movement by rendering it into a static image in two dimensions. Under a regime of private property, though, the discrepancy between the image and the moment diminishes the moment, and not the image, precisely because the image, and not the moment, can be owned. Experiences become images which may be exchanged for themselves ad infinitum while real moments, which cannot be exchanged, become distant and diminished as if seen through the viewfinder. “The system becomes weightless”.[10]

THE PHOTOGRAPHIC CONSCIOUSNESS

Alienation is central to the popularity of photography. Consider the different reception to two similar photo essays, Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives (1890), and Eudora Smithe’s All God’s Children (1885). Both documented the inhabitants of urban slums and both benefitted from recent photographic advancements. Riis was an early adopter of the magnesium flash, without which he would have never been able to properly expose photographs in the darkened slums of New York’s Lower East Side.[11] Smithe, an apprentice of Louis Daguerre, had improved the Daguerreotype process in such a way as to include both the photographer and the camera in the final image.[12] Riis’ work was published to critical acclaim and even prompted then Governor Roosevelt to improve sanitation and plumbing in New York’s slums. Smithe’s images of London’s East End, however, were met with outrage from the bourgeois photograph consuming community. A side effect of Smithe’s process was that her photographs included all of the subjective thickness and “elements in becoming” present in the moments they depicted, including the bourgeoisie themselves attempting to subsume those moments (via their images) into the regime of private property.[13, 14] She had reproduced a real moment when her audience wanted a photograph.

THE POLITICS OF SEEING

Reaction to All God’s Children underlines the social need to make distinctions between kinds of images. Before photography was legitimated as an art form, it existed as evidence of the world that, paradoxically, it produced. Such photography factualized. Images were deployed as evidence of the empirical fact of the rational world and its ideology. At the same time, such images came to constitute a mode of identifying reality itself: real is that which conforms to its image.[14] Smitheotype images do not look real despite being the most valid representations of the real in existence. The fact that the ghostly, streaking after-images of the bourgeois photo-buying public and the vague clouds of linguistic construction in Smithe’s work do not look real made it easy to dismiss them as unreal. There was, then, an aesthetic need to censor Smithe’s work. There was a political need to censor her work as well. Had it been taken as factual, All God’s Children would have destabilized the social fabric of 19th century western capitalism by implicating the capitalist class in the production of poverty. Such censorship is no longer necessary because images that threaten to destabilize a social order can be described as merely art.

TO DEMOLISH THE VISUAL

Photography can be a stage for a particular kind of conflict: the dialectical confrontation of vision and estrangement. It is tempting to say that all photography is science fictional because all images estrange real moments by reducing their subjective thickness into static, two-dimensional objects. However, that would be to forget that there are two orders of images: images which factualize and images which dissimulate. By canonizing photography as art, we separate factualizing from dissimulating images. On the one hand, this restricts some images’ ability to dissimulate. However, by granting the honorific “art” we put these images into conversation with truth, even as we remove them from conversation with fact. This is the great strength of art. It is not fact therefore it is not threatening. The nova that such images introduce are less threatening as art much as science fictional nova are less threatening as unserious genre literature. Because they are less threatening we admit these images into ourselves. We allow them to work us over. Images then have a duty to be more science fictional, to estrange more thoroughly and purposefully, and to do so not as mere objects of art, but as depictions of a real beyond fact.

1] Freedman, Carl. Critical Theory and Science Fiction. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press Published by University Press of New England, 2000.

2] Ibid

3] Dick, Philip. VALIS. New York: Library of America: Distributed to the trade in the United States by Penguin Putnam, 1981.

4] Ibid

5] Anderson, Benedict Richard O'Gorman. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 2006.

6] Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books.

7] Mieville, China. 2009. The City & The City. New York: Del Rey, 2010

8] Mirzoeff, Nicholas. Right to Look : A Counterhistory of Visuality. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2011.

9] Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001.

10] Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995.

11] Riis, Jacob A., Jacob August Riis, and Luc Sante. How the Other Half Lives. New York: Viking Penguin, 1997.

12] Nouveau et al. Histoire de la Photographie. Paris: Phaidon Press, 1941.

13] LeFaux, Guy. Images of Thought: Eudora Smithe and the End of Modernism. New York: Columbia University Press. 1990

14] Letters, Members to President of Société Des Amateurs de Photographie, 1886, The College du France Symposia Archives.

15] Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995.

16] McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: MIT Press.

2] Ibid

3] Dick, Philip. VALIS. New York: Library of America: Distributed to the trade in the United States by Penguin Putnam, 1981.

4] Ibid

5] Anderson, Benedict Richard O'Gorman. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 2006.

6] Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books.

7] Mieville, China. 2009. The City & The City. New York: Del Rey, 2010

8] Mirzoeff, Nicholas. Right to Look : A Counterhistory of Visuality. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2011.

9] Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001.

10] Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995.

11] Riis, Jacob A., Jacob August Riis, and Luc Sante. How the Other Half Lives. New York: Viking Penguin, 1997.

12] Nouveau et al. Histoire de la Photographie. Paris: Phaidon Press, 1941.

13] LeFaux, Guy. Images of Thought: Eudora Smithe and the End of Modernism. New York: Columbia University Press. 1990

14] Letters, Members to President of Société Des Amateurs de Photographie, 1886, The College du France Symposia Archives.

15] Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995.

16] McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: MIT Press.