HIC ET NUNC DIMITTIS

D.W. Burnam

January 2011

Our 3rd issue of LxWxH, titled Incorruptible View, took its name from a compelling phrase in DW Burnam's accompanying essay below. This lovely collaboration featured multiple original works by Amanda Manitach and Derrick Jefferies, and Burnam's captivating essay puts the works into a deep and far-reaching context.

There's a lot of good argument that art and thought are linked, equally that art skews the framework of thinking, if only to momentarily blur (some probably already misapprehended) information. Amanda Manitach's and Derrick Jefferies' deflected representations are feints that seem deliberately designed to provoke an initial, unedited, unskewed read and a ready connection to the existing phenomenal catalog. But, as is often the case in art, duration erodes assumption and bares endless agendas of the depicted to satisfy fully what is represented only partially. If a faithful representation in art serves the site it aspires to substitute and to which it points – away from itself – then these “missteps” lead back into the thick of the work, into its space, by constantly switching the referent's loyalty to the outside, back inside and then outside again. This toggle speaks to the empty index out of which both Amanda's and Derrick's visual vocabularies sprout.

Derrick's off-the cuff alchemy and Amanda's florid niello meditations picture the sine qua non – the twice-represented image of reality – and the fleeting apparition of prima facie thought itself. Their images lure and then arrest the mode of measurement that is a parasite choking the voice of the never-before-seen, extruding causes from effects; their images diligently mark the traces of heretofore uncatalogued material properties.

Both Amanda's and Derrick's work is hyper-rendered abstraction: so the image initially declares itself a replica but at such a remove from its original that it transmutes, through its appearing, the real materials of a dis/misplaced original. Their work suppresses image context. Like a mental map inverted, cognition stalls as it mis-sorts information, giving shape to a repository of associative compulsion.

Each builds representational diegeses (think Poe; think Shelley) upon encounters with the fleeting objectivities of their individual source material; representation in so far as it is 1) a support that renders the properties of light and mass in spatial simulacrum and 2) a temporal seam dividing the in/out of synchronicity with the present – but then with whole contexts, settings and place-names masked or altogether left out.

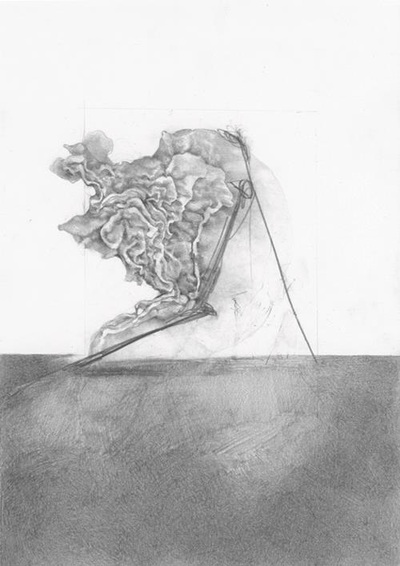

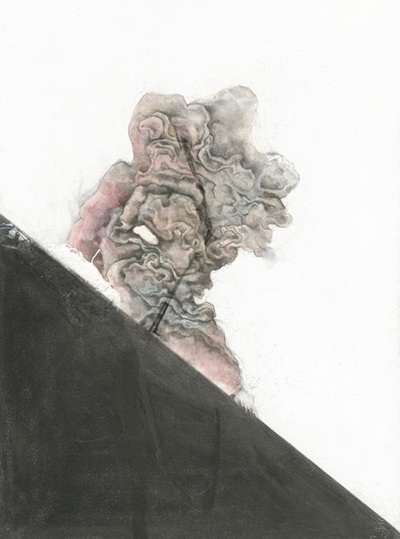

A baroque obsession with fabric folds, a predilection for repetition and a treatment of language that removes its certainty and imperative for destination add up to an awareness that Amanda's labor is almost overtly informed by a (para-)philosophical working-through; any of her products could stand as a materialization and formal intervention into complex (anarchic) inquiry. Viewing Amanda's drawings through the lens of the kind of literature that lays out this approach amounts to witnessing the effect/affect of a textual type, an investigation awash in exported research and neologism: a spaghetti-ing intercourse of willfully objective subjectivity, willfully subjective objectivity and layers upon layers of (mis-)translation.

Amanda's drawings transform their paper, dissolving it (not literally; still, somehow a physical reaction) into a kind of topical viscera, but the imprints of barriers and edges keep the dissolves from spreading to the corners. As metaphors these rigidities suggest an ever-present support: equal didactic structure and syntactical inhibition. The collision of hard and soft marks a site-specific threshold between a documented “text” and an actual event. From another standpoint (formal and art-historical) these opposites harangue the modernist mise en scene – you know: the scene without the mise – employing a reduced picture plane that sandwiches the pedestal and the proscenium into static disarray.

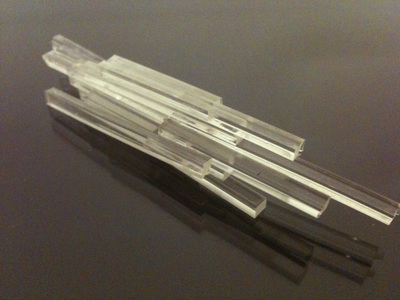

Derrick's task, in some respects, is to debase, displace and relocate the machine of the senses (register, compare, sort, file away) without scrapping the thing altogether. Photography's hopscotch of myth-making and truth-telling thrives here because, while theatrical focal intensity casts real objects in the light of fiction, these objects still avoid directives of tableau, like scale and environment, and ultimately remain pure documentation – though a document of what is always another question. Derrick over-considers the vernacular of his twofold formal network (sculpture/photo) so that the manipulable versatility of the “model” (quite often a live one in the sense of raw organic catalyzation) and the technical range and specificity of the camera combine in one seamless transition from disbelief to belief.

Derrick populates his studio with all manner of material investigation. Things grow on shelves, dry out on the sill, mold in a bag, stretch, secrete, fade, fuse, boil, break apart in innumerable ways and his photographs capture the creation and manipulation of whole new objects. Derrick's images draw a fierce bead on properties, a subject around which artists and scientists meet with probably almost equal discursive anxiety and effusiveness. A classic dichotomy, however, has scientific inquiry on one hand stringently adhering to a double line of observation and application that art, on the other hand, is always splitting apart. Art is taken to task for its preoccupation with the sense-in-itself and the thing-in-itself (as if there were some use for senses and things beyond their existence; the discrepancy probably has something to do with perceived occupational consequences). Naturally: to the engine of utility matter and minds aren't but fuel to burn, their effects observable only in the movements of a greater machine.

Derrick's and Amanda's excruciating attention to detail in all directions foregrounds the nascent activity of a hybrid image-object, a realization of the image that suspends the modernist shifter – the signification game of virtuality and actuality that simmers at the margins of the moment: where and in what context does thought ever allow anything its true form? “The vantage for thinking,” both artists seem to suggest, “is as much right here as it is in there or anywhere else.” But the question arises: how does one experience the world directly without negotiating it spatially, particularly when the increasing facility and imperative of omniscience mutates the (ever-overriding) faculty of sight into a fetishized myopia? Easy: culturally reified presence-at-a-distance, of course; extending the reach of the object, not the study. Two more questions, then: 1) is the remote ever direct? and 2) is this an act worth cultivating? will it destroy the universe?

[...]

It indeed always remains to be seen which end of the microscope of representation affords the incorruptible view. We live on a perpetual site of departure.

There's a lot of good argument that art and thought are linked, equally that art skews the framework of thinking, if only to momentarily blur (some probably already misapprehended) information. Amanda Manitach's and Derrick Jefferies' deflected representations are feints that seem deliberately designed to provoke an initial, unedited, unskewed read and a ready connection to the existing phenomenal catalog. But, as is often the case in art, duration erodes assumption and bares endless agendas of the depicted to satisfy fully what is represented only partially. If a faithful representation in art serves the site it aspires to substitute and to which it points – away from itself – then these “missteps” lead back into the thick of the work, into its space, by constantly switching the referent's loyalty to the outside, back inside and then outside again. This toggle speaks to the empty index out of which both Amanda's and Derrick's visual vocabularies sprout.

Derrick's off-the cuff alchemy and Amanda's florid niello meditations picture the sine qua non – the twice-represented image of reality – and the fleeting apparition of prima facie thought itself. Their images lure and then arrest the mode of measurement that is a parasite choking the voice of the never-before-seen, extruding causes from effects; their images diligently mark the traces of heretofore uncatalogued material properties.

Both Amanda's and Derrick's work is hyper-rendered abstraction: so the image initially declares itself a replica but at such a remove from its original that it transmutes, through its appearing, the real materials of a dis/misplaced original. Their work suppresses image context. Like a mental map inverted, cognition stalls as it mis-sorts information, giving shape to a repository of associative compulsion.

Each builds representational diegeses (think Poe; think Shelley) upon encounters with the fleeting objectivities of their individual source material; representation in so far as it is 1) a support that renders the properties of light and mass in spatial simulacrum and 2) a temporal seam dividing the in/out of synchronicity with the present – but then with whole contexts, settings and place-names masked or altogether left out.

A baroque obsession with fabric folds, a predilection for repetition and a treatment of language that removes its certainty and imperative for destination add up to an awareness that Amanda's labor is almost overtly informed by a (para-)philosophical working-through; any of her products could stand as a materialization and formal intervention into complex (anarchic) inquiry. Viewing Amanda's drawings through the lens of the kind of literature that lays out this approach amounts to witnessing the effect/affect of a textual type, an investigation awash in exported research and neologism: a spaghetti-ing intercourse of willfully objective subjectivity, willfully subjective objectivity and layers upon layers of (mis-)translation.

Amanda's drawings transform their paper, dissolving it (not literally; still, somehow a physical reaction) into a kind of topical viscera, but the imprints of barriers and edges keep the dissolves from spreading to the corners. As metaphors these rigidities suggest an ever-present support: equal didactic structure and syntactical inhibition. The collision of hard and soft marks a site-specific threshold between a documented “text” and an actual event. From another standpoint (formal and art-historical) these opposites harangue the modernist mise en scene – you know: the scene without the mise – employing a reduced picture plane that sandwiches the pedestal and the proscenium into static disarray.

Derrick's task, in some respects, is to debase, displace and relocate the machine of the senses (register, compare, sort, file away) without scrapping the thing altogether. Photography's hopscotch of myth-making and truth-telling thrives here because, while theatrical focal intensity casts real objects in the light of fiction, these objects still avoid directives of tableau, like scale and environment, and ultimately remain pure documentation – though a document of what is always another question. Derrick over-considers the vernacular of his twofold formal network (sculpture/photo) so that the manipulable versatility of the “model” (quite often a live one in the sense of raw organic catalyzation) and the technical range and specificity of the camera combine in one seamless transition from disbelief to belief.

Derrick populates his studio with all manner of material investigation. Things grow on shelves, dry out on the sill, mold in a bag, stretch, secrete, fade, fuse, boil, break apart in innumerable ways and his photographs capture the creation and manipulation of whole new objects. Derrick's images draw a fierce bead on properties, a subject around which artists and scientists meet with probably almost equal discursive anxiety and effusiveness. A classic dichotomy, however, has scientific inquiry on one hand stringently adhering to a double line of observation and application that art, on the other hand, is always splitting apart. Art is taken to task for its preoccupation with the sense-in-itself and the thing-in-itself (as if there were some use for senses and things beyond their existence; the discrepancy probably has something to do with perceived occupational consequences). Naturally: to the engine of utility matter and minds aren't but fuel to burn, their effects observable only in the movements of a greater machine.

Derrick's and Amanda's excruciating attention to detail in all directions foregrounds the nascent activity of a hybrid image-object, a realization of the image that suspends the modernist shifter – the signification game of virtuality and actuality that simmers at the margins of the moment: where and in what context does thought ever allow anything its true form? “The vantage for thinking,” both artists seem to suggest, “is as much right here as it is in there or anywhere else.” But the question arises: how does one experience the world directly without negotiating it spatially, particularly when the increasing facility and imperative of omniscience mutates the (ever-overriding) faculty of sight into a fetishized myopia? Easy: culturally reified presence-at-a-distance, of course; extending the reach of the object, not the study. Two more questions, then: 1) is the remote ever direct? and 2) is this an act worth cultivating? will it destroy the universe?

[...]

It indeed always remains to be seen which end of the microscope of representation affords the incorruptible view. We live on a perpetual site of departure.